Backlog Goddag Letter, Diwali Days, 26 October 2025

My long Diwali celebrations of 2025 had been some of the most memorable and spontaneous days in a while.

I believe Diwali started early for me, on the 15th of October. After learning, upon arrival at NDLS, that my train to Gorakhpur was severely delayed, I tried to find a calm spot on the platform to pass some time. Walking towards the end of the platform, I found an area with barely any people except for two cheerful police ladies chatting. I took a seat close to them and started reading Kierkegaard’s Purity of Heart. Eventually, the police ladies moved off, leaving room for a drunk old man. He stared intensely at me, far more intensely than the perpetual gaze foreigners receive in India. I just carried on reading. The section I was reading was about maturing and the lack of being able to go further than the eternal:

“For in relation to the Eternal, a man ages neither in the sense of time nor in the sense of an accumulation of past events. No, when an old person has outgrown the childish and the youthful, ordinary language calls this maturity and a gain. But willfully ever to have outgrown the Eternal is spoken of as falling away from God and as perdition and only the life of the ungodly ‘shall be as the snail that melts as it goes.’”

Only seconds after being struck by this passage, Diwali kicked in: a young open guy sat down beside me and started talking. Abhishek was his name. I immediately had a good feeling talking to him. He asked me why I didn’t move away from the drunk guy staring at me, nor the trash right next to me. It hadn’t bothered me too much. Then the old drunk guy walked up to us and asked us for food. I only had my sourdough bread on me, which I shared with him. I don’t think he really liked it… As the man started shivering when eating the sourdough bread, Abhishek told him to stop bothering us.

We sat down a few meters further and exchanged our life stories. It felt surprisingly comfortable chatting with him. He invited me for Diwali to his house, we checked trains, and that was it: I was going for Diwali to Bagaha! We were in different train compartments and would reconnect the next morning. Meanwhile I chatted with Arpita, a wonderful girl I met that booked the same train cabin as me.

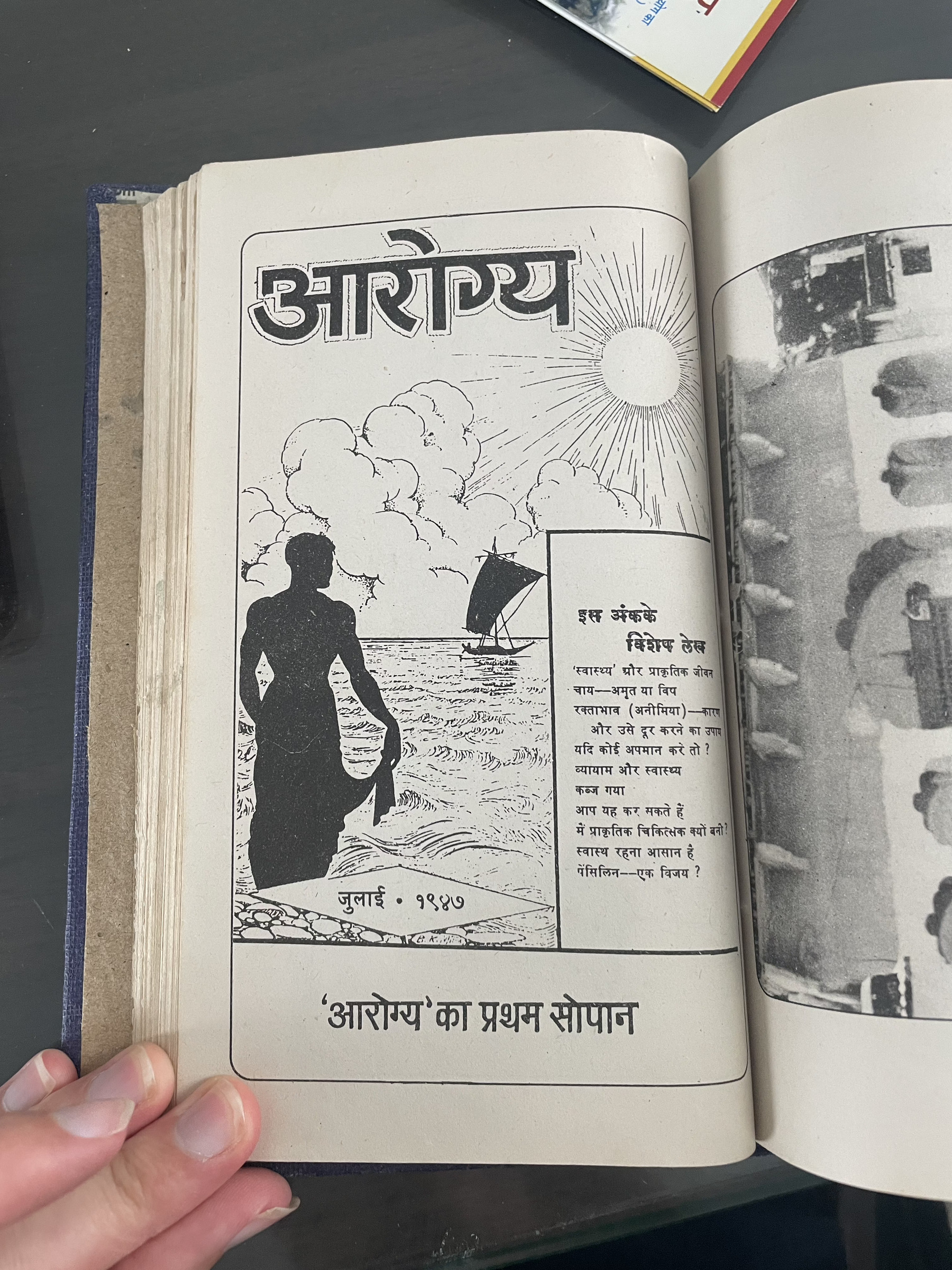

Before going to Bagaha, I was doing my research in Arogya Mandir, a health ashram by the revolutionary Vithal Das Modi (this will get a separate blog!).

That weekend I went on the Vande Bharat to Bagaha, where I found Abhishek and his father. They drove me to his house. In no time, I had met his entire family, who were lovely. The person who fascinated me most was Abhishek’s grandfather, who was reading the Gita and other smriti books in a little shed in front of the house. He had given all this land that he had bought relatively cheaply from the Britishers, when they suddenly had to leave in 1947… Since he couldn’t pay everything in one go, he even still transferred money after they had long left (unimaginable now!). For several years now, he had fully devoted himself to God. The family and I cooked together, held pujas together, made flower rangolis, lit diyas, and much more. The hospitality was, in every sense, overwhelming.

The next day we explored Gandhi’s ashram, where he began his first Champaran Satyagraha against unfair indigo trade, and then visited some remaining Ashoka Pillars with Abhishek’s uncle. Quite soon I had to leave as I had already booked a journey to Ahmedabad from Ayodhya.

Before arriving at Ahmedabad, I stopped by the new Ram Mandir, at the site believed to be the birthplace of Lord Rama. The Ram Mandir has only recently been officially completed (25 Nov 2025). There had been tension around its construction, as it had followed the destruction of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

In Ahmedabad I was welcomed in the beautiful family of Jagdip Mehta, a family of musicians who did performances together, and the twin daughters did regular national and international tours. The “heritage home” that they live in is a stunning house that the family renovated around 2008, featuring a 16th-century Italian-designed ceiling in front of the room I was sleeping in! My days in Ahmedabad shifted between visits to the archives at Sabarmati, with its wonderful archivists (separate update!), and time with the Mehta family. We ate together, cracked Diwali fireworks, played card games, and sung devotional songs. Especially the youngest, Shivaj, a big fan of the YouTuber Mr. Beast, was such a lively character with a promising future ahead of him!

Unearth Kāla #1 Queen Huh (?) Memorial Park

Hei, god dag,

This is my first Unearth Kāla Post. I called it Unearth Kāla, because Kāla is a sanskrit term meaning “death” or “time” and I am unearthing dead time here :). In these posts I share notes on things I find out about a place, object, or event that surprise me and I had no clue about before. Maybe you didn’t know it either, and if so, help with your memory so that it is not forgotten…

20.10.2025

In between all the warm Diwali celebrations, I bumped into the first historical “foundling”, which is actually hard to miss when you are in Ayodhya: Queen Huh (?) Memorial Park. While Ayodhya is mostly visited now because of the new Ram Temple constructed on the site where the Babri Masjid stood until 1992. Nestled between the bustle of Sarayu Ghat, Ram Ki Paidi, and a new construction site for who knows what, there is a garden with a pavilion dedicated to Korea-India ties that, it is said, stretch back 2,000 years!

When I walked into the garden, the first thing I noticed is poor spatial harmony. But if you walk over the bridge, there sits a beautiful pavilion reflecting the Joseon-architectural style of Changdeok Palace! So many questions came to mind, but crucially: why is there, in the middle of Ayodhya, a Joseon-style pavilion?

The answer merges myth with history. According to Il-Yeon’s “Samguk Yusa (1281)”, King Suro, the legendary founder of the Gaya confederacy 2,000 years ago on the Korean Peninsula, married Princess Suriratna of “Ayuttha”. The plaque next to the Korean Pavilion concludes, in Korean, Hindi, and English, that Suriratna, after a divine dream, must have sailed “4500 km across the sea to become the Queen of Garak”.

However, when I first heard the name Ayuttha, I immediately thought of an entirely different city almost 2000 km east of Ayodhya: Ayutthaya! It turns out there is an ongoing scholarly debate on where Queen Heo Hwang-ok truly came from. Rana P.B. Singh and Sarvesh Kumar give a nice overview of it in Interfacing Cultural Landscapes between India and Korea. In 2000, Ayodhya and Gimhae were designated as sister cities. In 2001, a Korean delegation allegedly accompanied by the North Korean ambassador to India came to inaugurate the memorial. As hinted at in the chronological overview, over the years the park has gone through various remodelings.

Backlog Goddag Letter, 18 October 2025, Arogya Mandir

God dag!

A letter from 18 October 2025:

“The next stop, I am getting off of this train - no matter what!” I said, fully determined. Abhishek glanced up and mumbled: “And they call it Gorakhpur Express… Arpita said nothing. The three of us were stuck together by the shared ordeal of Indian Railways. The twelve-hour delay affected Abhishek and Arpita much more: they missed their connection, with family waiting back home to celebrate Diwali. Stragenly, though, it felt as if only my patience with the train system wearing thin…

As we were rolling stepfoot into Domingarh, a ten-minute ride from our destination, Abhishek suddenly stood up and, without warning, jumped off our train. “See you in Bagaha!” he shouted as he disappeared into the thick smoke surrounding Domingarh. “Floris, don’t get off, this neighbourhood isn’t any good… look around, there’s absolutely nothing but dust and garbage!” Arpita argued. Looking outside you could indeed hardly see an actual station. I agreed with Arpita, I could not leave here. Indecision kept clouding my thought process, uncertainty about where I would sleep the night, and all my former resolve had gone up in thin air.

Eventually, the train started moving again and barely ten minutes later we arrived in Gorakhpur. I took an auto to Arogya Mandir. Though Gorakhpur was full of life at midnight, Arogya Mandir seemed fast asleep when I arrived. Founded in 1940 by the non-violent resister Vithal Das Modi, Arogya Mandir is a naturopathic ashram. I had come to study its ideas on naturopathic non-violence and its role in India’s independence movement. But when I arrived, I found the gate firmly shut. Just as worries about the night began creeping in, I spotted a guard at the far end of the wall. He asked whether I had an appointment with Vimal Modi. I nodded, and moments later the beautiful wooden doors opened. A gentle, well-kept man stood before me and said: Don’t excuse yourself for being late, the train is outside of your control. Little did I know that he was the son of Vithal Das Modi himself, the revolutionary naturopath who founded Arogya Mandir. Feeling embarrassed of how unkept, and probably how smelly (!), I was after my long train journey, I kept my tick jacket tightly closed. He put me at ease, offered me a room, and suggested I freshen up. We would talk in the morning.

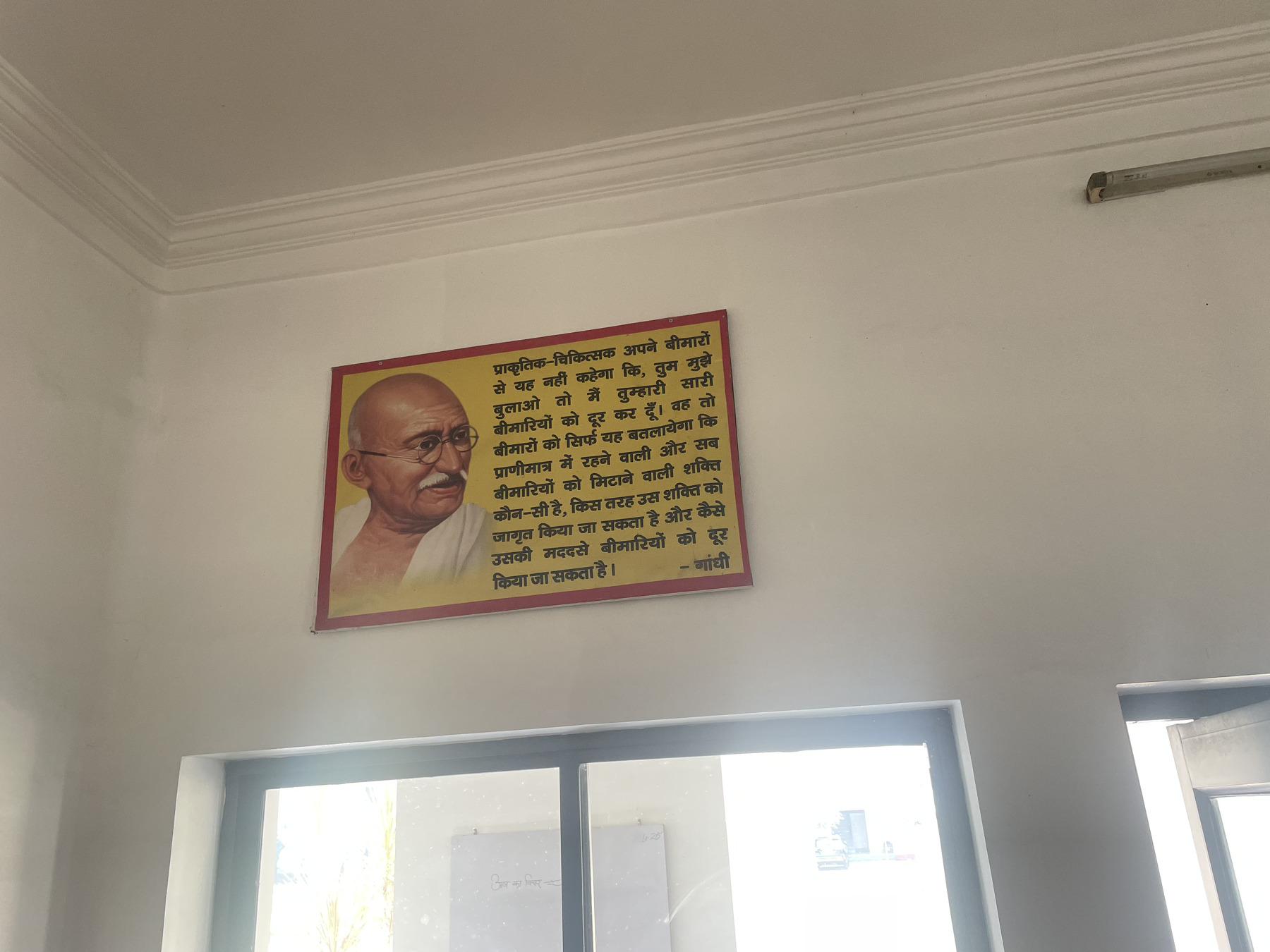

I reported at six in the morning., and with the others I shared a cup of tea before starting to walk on the circular mud path beside the dormitory corridors. My fellow path walkers looked visibly surprised to see me. Vimal Modi soon walked next to me and we began talking. He spoke about his father, appeal of the naturopathic lifestyle, his meetings with Gandhi, and his own pride in the centre. Insisting on the non-violent nature of naturopathic treatment, he was careful to separate it from politics. “Gandhi requested Vithal Das Modi to only focus on naturopathy, not politics”, he explained. He was equally glad to hear why I came.

After the walk a light nature cure breakfast awaited me: fresh papaya, walnuts, and sprouted greens. Treatment then began for the “patients”, with heat packs, mud packs, steam baths, and enemas. The last one I politely declined… After some persistence, I received access to the library, where I read more about Vithal Das Modi’s non-violent activities and the ashram’s role in sheltering revolutionaries. Old photographs of Gorakhpur were in the books. As Vimal had mentioned in the morning, before independence Arogya Mandir stood on the city’s outskirts, in quiet nature. Over time, the city, with all its noise and pollution, had crept closer to the ashram. And yet, as a Buddhist monk from Arunachal Pradesh told me over dinner, no ashram set in such chaos ever keeps this kind of calm!

A few nights at the ashram indeed left me feeling recharged with energy, something that would turn out vital for the wild Diwali days that were to come!